The Living Standard logo mark is centered around a warm triangle cutout that highlights an arrow for forward progress and showcases the promise of a new horizon. When I first saw the icon unveiled by the U.S. Green Building Council, something about its shape resonated with me, but I couldn’t put my finger on what. After a few minutes of staring and skepticism, I started to connect the dots.

Me at 4 years old in 1979.

As a young girl growing up in Texas in the ‘70s and ‘80s, my favorite outfit was a tightly wound set of pigtails, my Wonder Woman Underoos, baby blue corduroy bell bottoms, and a pair of brown cowgirl boots. During long summer days on the kickball field with friends, we thought nothing of the hazy brown sky or the pungent smells of rotten egg that wafted through the neighborhood day in and day out.

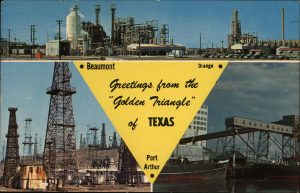

If you’re trying to imagine what I’m talking about here or liken it to something you’ve seen before, think about the flaxen look of Erin Brockovich. Think about warm tones, long balmy mornings and afternoons, and communities blissfully unaware of the pollutive undercurrent grumbling between Beaumont, Orange, and Port Arthur. This was southeast Texas, the oil and gas epicenter of the United States just minutes from the Gulf Coast and the Louisiana border — otherwise known as the Golden Triangle.

The Living Standard logo.

The Golden Triangle in Southeast Texas.

Looking back, I understand now that I grew up in a fairly apolitical household. For a combined 75 years, my parents worked at oil refineries in this famed part of the state; and as a family, we knew very little about our rights to a clean environment, and about political accountability, and corporate responsibility. These just weren’t the conversations we were having. In fact, even with that information more accessible today, most members of my extended family living there still work at local refineries and chemical plants because they have kids to support and it’s one of the only well-paying gigs in town.

I don’t blame them.

Companies haven’t always made it easy for people to access information around environmental injustices and inequality. The decisions people make around both consumerism and employment are often between planet and profit, creating a vicious cycle between company and consumer, between employer and employee — when in reality, making money and creating a healthy living standard can go hand in hand.

That’s what I set out to do in my career in sustainability — to make a living at making a better standard of living for people across Texas.

Fighting off “bag monsters” while giving a press conference at the Texas Capitol in 2011 to defend local bag bans across the state.

In 2003, I cut my teeth in activism at an environmental non-profit committed to eliminating toxic electronic waste (e-waste) across the state. We went door-to-door all across Texas to build community support, which spurred our policy collaboration with Dell, Thompson, and Samsung to pass historic, statewide legislation that has since kept over 300 million pounds of e-waste out of Texas landfills. I organized thousands of residents to do the very thing I wish someone had done for my family and my neighbors growing up: demand public health protections from those in power and to publicly hold corporations accountable for their role in polluting the state.

Since then, I played a key role in passing City of Austin ordinances regulating business recycling, single-use plastic bags, residential curbside composting, and construction debris recycling. In 2015, the Austin City Council appointed me commissioner to its Zero Waste Advisory board where I served two years vetting waste diversion policies for Council consideration.

But after years of this work, in 2013, I came to a personal fork in the road. It dawned upon me, perhaps later than it should have, that I had gotten caught up in the idea of being anti-pollution. I had made it a very binary issue, often talking publicly and recruiting others in protest without considering that polluting entities came with complicated human stories that required more granular discussions and forms of activism. I thought to myself, “Why had it become all about sticking it to the man? Why had I offered up more public insults than public policy and ideas? Why had I made it about shaming companies, who, whether I admitted it at the time or not, were run by very real people with friends and families living in communities they cherished — people just like my own parents, friends, and family, in the Golden Triangle?”

That’s when things changed for me.

Careful not to spend this personal reckoning shaming myself, I saw it as an opportunity for growth. I’d developed deep relationships with City Council members and their aides, the environmental heavy hitters in Texas, and the landfill, recycling, and composting haulers in the area. This was an entrepreneurial chance for me to position myself as a resource, as the “Go-to Green Gal” in Texas.

So, that’s exactly what I did. I remembered why I loved this work in the first place — that it was about changing the quality of life for people who didn’t even know that was an option, let alone something that was achievable in their communities. I bootstrapped over $20K, spent hundreds of hours getting my business up and running, and gained hands-on experience implementing cost-saving waste diversion protocols. I was determined to be a valuable resource in shaping corporate social responsibility instead of complaining that it wasn’t getting done in an efficient and innovative manner.

In my experience, businesses have paid lip service for far too long on sustainability. When it comes to reducing waste for increased revenue, they either don’t know where to begin, have good intentions but are too overwhelmed, or worse, they already have programs in place without funding or enforcement.

But more often than not, what they really want to do is empower their employees and lead their industry through green transformation. Their biggest challenges revolve around profitability of recycling vs. landfilling, lack of employee education and buy-in, and executive mandates with no support. And that’s where my company, Zero Waste Strategies, comes in.

In 2018, Zero Waste Strategies led nine business waste audits to give Dallas City Council a cross-sectional view of the state of recycling.

When companies work with us, we alleviate their pains around these issues and lead the charge to “go green” from the inside out. In addition to our work with AT&T, Dell, Kohler, and Nestle Purina, Zero Waste Strategies holds membership status in the Austin Green Business Leaders program, the U.S. Green Building Council, multiple Chambers of Commerce, and has served thousands of businesses through our municipal contract with the City of Austin.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we are providing online training programs for professionals who deal with business waste matters. This way, they can head back to the office confident and prepared to effectively implement company sustainability policies.

I’m hoping that my time in the Golden Triangle inspires others to connect the dots of their sustainability story — and to figure out how their own life can be a key ingredient in creating a better standard of living for all.

Stacy Savage is founder and president of Zero Waste Strategies.

About Zero Waste Strategies

Zero Waste Strategies (ZWS) is a premier sustainability consulting firm focused on Zero Waste protocols to support the new Circular Economy. ZWS works with industry leaders who are serious about using waste reduction to drive increased revenue, deeper customer loyalty, and a green marketing edge.