The pandemic is revealing vast systemic inequities in countries around the globe. And while the approaches to protecting human health and wellbeing vary from region to region, one unfortunate reality is echoing in communities across the world:

In the absence of government accountability and unified public health policies that could adequately address the intersections of climate change and COVID-19, educators are being forced to handle everyday obstacles with their own ingenuity — and often their own pocketbooks.

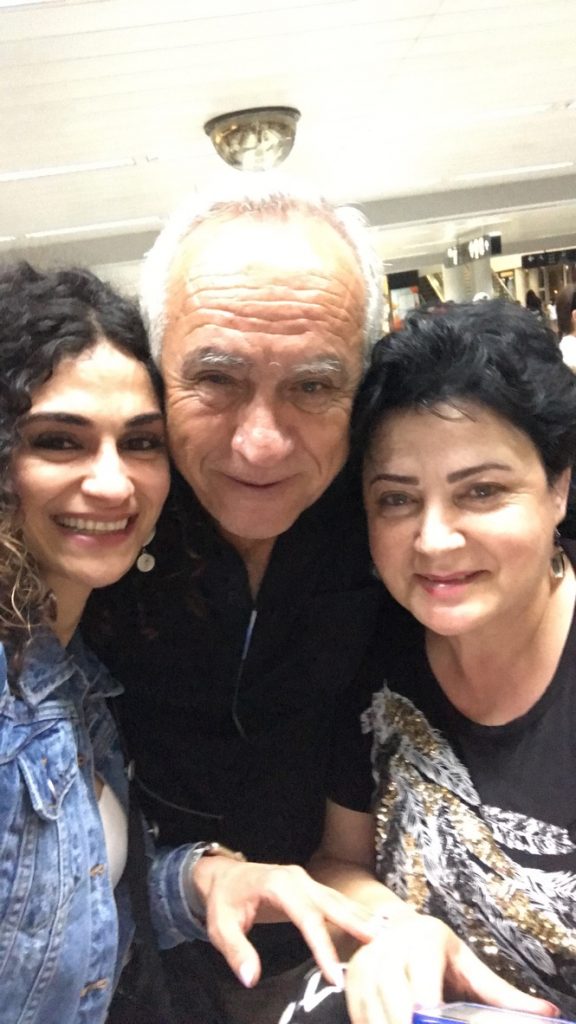

My mother, Hassiba Hallal, is a teacher in Ghazieh — a town located in South Lebanon. She holds a bachelor’s degree in history and for decades, taught kindergartners. But in 2012, after the onset of the war in Syria, an urgent need arose inside the school for improved health services and health communication. It was my mother who stepped up.

My mother, Hassiba Hallal, is a teacher in Ghazieh — a town located in South Lebanon. She holds a bachelor’s degree in history and for decades, taught kindergartners. But in 2012, after the onset of the war in Syria, an urgent need arose inside the school for improved health services and health communication. It was my mother who stepped up.

Taking on the responsibility of managing the health of students in any community is a tedious and complicated position to say the least — but in South Lebanon, the access to resources is much scarcer than what we often take for granted here in the United States. And that’s before taking the pandemic into account.

Fast forward to 2020.

Electricity is still only available 12 hours a day and it is rationed and distributed over the course of a 24-hour period. And while there is some local electricity generation, it is not a reliable option.

The basic air filters you can find in almost any supermarket or hardware store in the United States are nowhere to be found.

And while the initial COVID-19 guidelines my mother was asked to educate others on and enforce within the school included social distancing, masks, and hand washing — airborne strategies were noticeably missing. Additionally, there was significant confusion around the effectiveness of face shields, tunnels, sanitization, and more.

While facing these challenges, my mother and I have spent numerous hours on WhatsApp discussing strategies she could employ to safely re-open the school.

With a very tight budget, it was critical to spend the money where it mattered the most. She tried creating a filter from scratch and strapping it to fans. Her first attempt was not successful, but with each effort she learned more and more.

Because we have more detailed resources specifically created for schools here in the U.S., I was able to translate many of them to Arabic for her (she was educated in French and does not speak English)

As an engineer, and a co-author of three new LEED Safety First Pilot Credits, I’ve used what I’ve learned here to help her address the challenges she faces in Lebanon. Earlier in 2020, a colleague, Larissa Oaks, and I drafted three new credits for how to re-open safely, pandemic mode for new construction buildings, and building maintenance and commissioning.

In 2017, I chaired the LEED Indoor Air Quality Procedure Pilot Credit that was successfully published — one for existing buildings and one for new construction. The intent of these credits is to reduce potential adverse health impacts to building occupants arising from exposure to indoor air compounds, and to contribute to the comfort and well-being of building occupants by minimizing indoor air quality problems associated with construction and renovation. You will often see me carrying sensors around and testing equipment or practices — and I am currently helping friends in Austin, Texas to test ionizers (which are marketed as a magic bullet to cure all indoor air quality issues) installed in their HVAC system. I am also working to create pandemic and emergency response plans to reopen safely for various types of spaces, including schools, universities, theaters, and offices.

All of this work has proved invaluable to the conversations with my mother and the subsequent improvements she has been able to make for her students.

LEED fills a critical gap in building codes, and its impact on building healthier spaces, enabling healthier lives, and contributing to a healthier economy has informed so many of the most productive sessions my mother and I have conducted during the pandemic. Because LEED has taken the approach of allowing and encouraging performance-based design and strategies that go above and beyond minimum standards, while at the same time keeping buildings accountable through frequent reporting of indoor air quality, I am optimistic about the seeds of its principles being planted in communities like Ghazieh, and I am hopeful that one day, we will see its mainstream adoption there.

I don’t like that educators like my mother have often been left unassisted in the wake of vast leadership vacuums and dwindling budgets, but I believe that through science and helping each other understand the myths about indoor air quality and energy efficiency, we can protect homes and schools where kids are subjected to harmful contaminants and more specifically to widespread community infection.

The challenges my mother faces show no signs of slowing down. With nearly 80 million displaced people in the world, we are witnessing the intersection of the biggest humanitarian crisis since WWII and the most significant public health crisis since WWI. Lebanon, which has the world’s highest per capita refugee population, has been particularly affected by an influx of more than one million Syrian refugees. The surge has taxed local resources, especially schools like my mother’s, and has affected both refugee children and Lebanese students. For many years, Lebanese public schools have been open extra hours to welcome displaced Syrian children. From 7:30am to 2pm, it’s a normal day for Lebanese students and some foreigners; then from 2pm to 7pm, it’s the Syrian refugees’ turn to learn. During those years, my mother worked double shifts to serve both Lebanese and Syrian kids. And now, COVID-19 has only compounded the already strained system.

They say that necessity is the mother of invention — and in my mother’s case, that is absolutely true! And it is both her inventiveness and her pragmatism that inspire me to keep doing my own work here in the States — and to share those best practices with others as much as possible.

They say that necessity is the mother of invention — and in my mother’s case, that is absolutely true! And it is both her inventiveness and her pragmatism that inspire me to keep doing my own work here in the States — and to share those best practices with others as much as possible.

She says, “The school is all that is left for those kids.”

She’s right — and I’ve heard that here as well — especially when we talk about the millions of American schoolchildren who, without in-person classes, are now food insecure.

I’m proud of the tireless effort she has put in, of her dedication to refugee and Lebanese children, of her spending countless hours with me solutioning for airborne COVID-19 concerns, and of her commitment to raising the quality of life for her students, her school, and her community as a whole.

The connective tissue of compassion I’ve witnessed in her and other educators around the world is something to aspire to — every day, not just during the pandemic.

I never really thought about sustainability from the perspective of having it bring me closer to my mother, of having it reveal things I admire in her more now than ever.

But it makes sense that the unexpected would present itself in 2020, of all years.

The perspective she has given me is immeasurable.

The pandemic has pulled us all apart in so many ways that would have been unimaginable even a year ago. But in the case of my mother and me, it has also allowed us to build relationships, to find commonalities in our struggles, and to share the resources, educational materials, and living standards every human being should be able to benefit from today and for generations to come.